Click on the image to download the pdf

For decades, women’s football was banned in Brazil. Now ex-drug traffickers are tackling prejudice in the game by training future soccer stars from the favelas

Vocabulary

Read and check you understand this before you read and listen to the article:

ridden: excessively full

stray: not in the right place; separated from the group or target

dodge: avoid (someone or something) by a sudden quick movement

impoverish: make (a person or area) poor

shootouts: a decisive gun battle

lack: the state of being without or not having enough of something

council estate: area of houses built and rented out to tenants by a local council

to cope: (of a person) deal effectively with something difficult

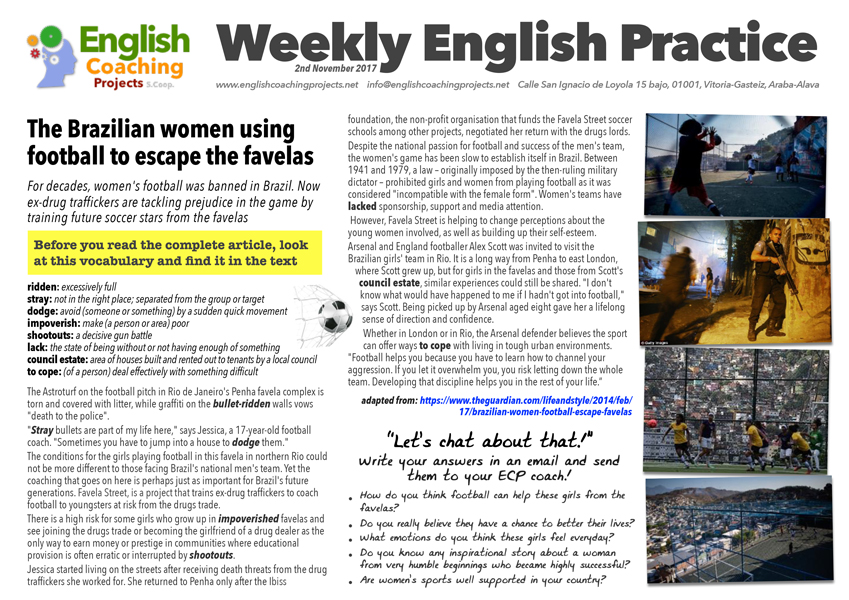

The Astroturf on the football pitch in Rio de Janeiro’s Penha favela complex is torn and covered with litter, while graffiti on the bullet-ridden walls vows “death to the police”.

“Stray bullets are part of my life here,” says Jessica, a 17-year-old football coach. “Sometimes you have to jump into a house to dodge them.”

The conditions for the girls playing football in this favela in northern Rio could not be more different to those facing Brazil’s national men’s team. Yet the coaching that goes on here is perhaps just as important for Brazil’s future generations. Favela Street, is a project that trains ex-drug traffickers to coach football to youngsters at risk from the drugs trade.

There is a high risk for some girls who grow up in impoverished favelas and see joining the drugs trade or becoming the girlfriend of a drug dealer as the only way to earn money or prestige in communities where educational provision is often erratic or interrupted by shootouts.

Jessica started living on the streets after receiving death threats from the drug traffickers she worked for. She returned to Penha only after the Ibiss foundation, the non-profit organisation that funds the Favela Street soccer schools among other projects, negotiated her return with the drugs lords.

Despite the national passion for football and success of the men’s team, the women’s game has been slow to establish itself in Brazil. Between 1941 and 1979, a law – originally imposed by the then-ruling military dictator – prohibited girls and women from playing football as it was considered “incompatible with the female form”. Women’s teams have lacked sponsorship, support and media attention.

However, Favela Street is helping to change perceptions about the young women involved, as well as building up their self-esteem.

Arsenal and England footballer Alex Scott was invited to visit the Brazilian girls’ team in Rio. It is a long way from Penha to east London, where Scott grew up, but for girls in the favelas and those from Scott’s council estate, similar experiences could still be shared. “I don’t know what would have happened to me if I hadn’t got into football,” says Scott. Being picked up by Arsenal aged eight gave her a lifelong sense of direction and confidence.

Whether in London or in Rio, the Arsenal defender believes the sport can offer ways to cope with living in tough urban environments. “Football helps you because you have to learn how to channel your aggression. If you let it overwhelm you, you risk letting down the whole team. Developing that discipline helps you in the rest of your life.”

“Let’s chat about that!”

Write your answers and send them by email to your ECP coach. Give reasons for your answers. Why not record your voice too? Listen to yourself speak and identify what you have to improve on 🙂

- How do you think football can help these girls from the favelas?

- Do you really believe they have a chance to better their lives?

- What emotions do you think these girls feel everyday?

- Do you know any inspirational story about a woman from very humble beginnings who became highly successful?

- Are women’s sports well supported in your country?

adapted from: https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2014/feb/17/brazilian-women-football-escape-favelas